Therapy Isn't Funny

On the Unbearable Seriousness of Much Modern Comedy

Comedians need to know their place.

The good ones do. They know their role is to lighten the load of existence, make things bearable. This is especially true of the comics who venture into the dark nether regions of the soul.

I’m not even just talking about stand‑up, a form of comedy of which I’m not a huge fan (and I would venture to say is quite Neo-Passéist), but anyone who deals with the comedic: writers, artists, filmmakers, satirists. Laughter is not a moral stance but an autonomic event, more like a sneeze than a sermon.

But there’s a problem that has afflicted mostly stand‑up comedians, and increasingly every other kind of comic worker: a lack of belief in the vitality of comedy itself. In order for a piece of media to be important, it cannot just be funny. It needs a dark edge. It needs to confront the audience. It needs to implicate “society,” undermine “patriarchy,” or genuflect toward some other prefabricated shibboleth. The Fool must have his footnotes.

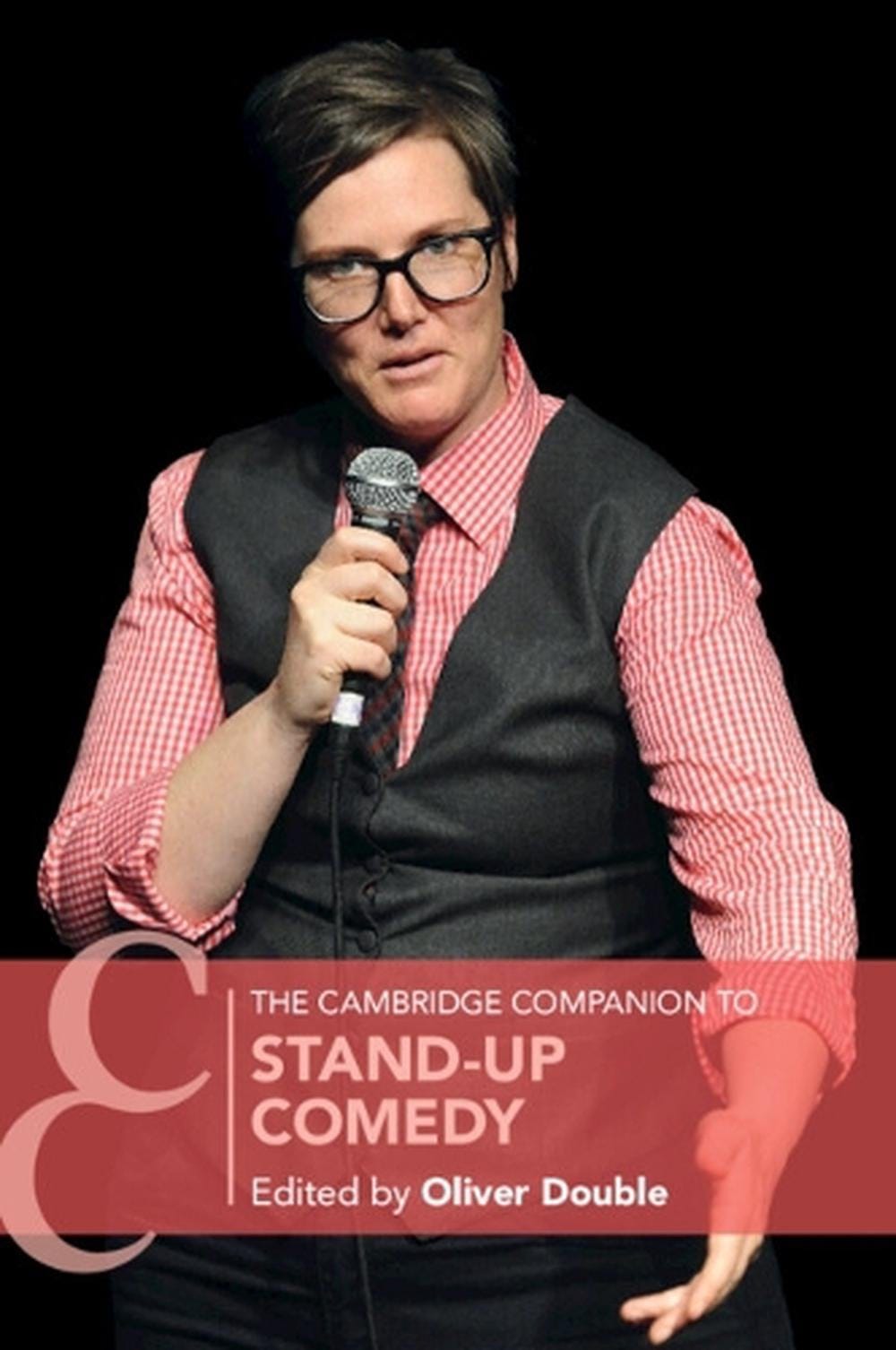

Whether it’s morbid Tasmanian lesbians haranguing you about their sexual assault, or black comedians going “anti-woke”, or TDS-afflicted skit shows, comedians need to remember jokes are not a delivery system for correct opinions.

Often, this tendency toward “seriousness” is a play to secure legacy. This comedian, by going on a 40 minute diatribe with no jokes but plenty of pathos, is doing something INNOVATIVE with the form. Well, no. What they’re doing is actually mistaking forms and playing into one of the oldest confusions in the Western tradition: that tragedy is artistically lofty while comedy is low.

One theory for this regrettable aesthetic assignation that I quite like: Aristotle’s book on comedy in the Poetics was lost, and the book on tragedy was not. Therefore, the tragic became an unduly privileged mode.

But tragedy operates at the scale of the human. Its figures might be mythical in stature, but they are legible and continuous with ourselves. Kings fall, families are destroyed, errors cascade into catastrophe. The emotional force of tragedy depends on nearness: this could be you. Pity and fear arise because the suffering remains meaningful.

Comedy requires something closer to divinity. When Aristotle says comedy represents people “worse than average,” he does not mean morally corrupt. He means ontologically reduced. Humans seen from a height at which their self-understandings no longer hold. Comedy abstracts us. It flattens intention into habit and passion into tic. From this altitude, our lives resolve into amusing patterns rather than singular stories. Comedy approximates a view from Mount Olympus: distant, amused, unseduced by our appeals.

Tragedy sanctifies suffering, while comedy profanes it. It doesn’t deny pain, but it does deny its singularity.

Of course, comedians are not Olympian gods. Far from it! A good looking comedian, when they exist, is rarely funny. But whether hideous or average-looking, they are ideally messengers for the Olympian perspective.

So while they channel the god-like delight at paltry mortal affairs, they are not situated above the human. The comic spirit allows them to see us as the gods see us: silly, ridiculous, laughable. The moment the comic insists on being morally inside the drama, the gods descend to ground level, transcendence evaporates, and comedy loses its mythic power.

Getting ahead of the objection: yes, I am aware that the tragi-comic blends both modes. But think about the successes here. By and large, the artist usually has to make a choice about what “outlook” they will privilege. Will the narrative resolution redound to the merely human or the Olympian chortle?

When comedians insist that their work must be taken seriously, they are not elevating comedy. The result is neither tragic nor comic, just overdetermined, humourless, and faintly coercive.

In Current Thing world, artworks are not meant to be experienced but to be understood. They present themselves like people in therapy, seeking acknowledgement. The artwork is a proxy self, incomplete unless witnessed, validated, and gently affirmed.

This is therapy art: art as disclosure, art as coping mechanism, art as public processing. Its highest ambition is not form or pleasure but recognition. Do you see me? Do you understand what happened to me? Do you agree that this pain matters?

There is so much of this now, and that’s why so much of everything is garbage.

Art should be made by people indomitable in their vision, people who seek to impose their work on the world, not negotiate with it. Art is not an exorcism. It is not a healing circle. It is an object, with edges, that either works or it doesn’t.

Comedy suffers especially under this regime because it is now expected to care in the approved way. Jokes must punch up, must signal empathy, must announce their ethical credentials before they are allowed to exist. The comic becomes a junior therapist, guiding the audience through shared trauma while carefully avoiding the wrong laughs.

But comedy is not empathy training. It is not there to validate your feelings. Often it does the opposite: it reveals your feelings as excessive, melodramatic, absurd. That is its gift.

Seen this way, therapeutic comedy is best understood as a collapse into moral immanence. Where comedy once relied on a vantage point from which human seriousness could be rendered strange, it is now required to remain embedded within the moral field of the present moment.

Audiences, then, are moral subjects to be addressed rather than embodied creatures to be surprised. Laughter is no longer something that happens to us, that we can’t help. It becomes something we must agree to in advance. This is symptomatic of what Alice Gribbin calls the empathy racket:

“Readers and audiences are flattened into ‘members of society’ by the empathy fixation, stripped of their all-too-human parts to which society is blind. But society had to be invented. It does not contain the human experience. Marxists and critical theorists, like social-engineering empaths, misunderstand this. We are not social beings only, acted on by power structures. There is more to existence than our emotional connection with or responsibilities to others.”

Therapeutic comedy accepts the social totality as final. It refuses any vantage point beyond it. The comic artist becomes a moral participant rather than a metaphysical irritant, tasked with affirming the audience’s ethical self-image rather than disturbing it.

This is why so much contemporary comedy feels airless. There is nowhere for the joke to go. Everything remains on the same plane: injury, acknowledgment, reassurance.

Christopher Lasch saw this coming. In The Culture of Narcissism, he describes late-twentieth century society as drenched in therapy language, which has replaced older moral and aesthetic vocabularies. The self becomes fragile, perpetually injured, in need of constant affirmation.

Under these conditions, art no longer challenges or overwhelms the individual, it consoles them. The artist becomes a fellow sufferer, not a maker of worlds. Expression replaces craft, while sincerity replaces skill. Therapeutic comedy reassures rather than surprises. It seeks applause for its intentions rather than laughs for its timing or its surprising incongruity. It wants credit for being aware, or dare I say, for being woke.

A good joke will always rearrange the air in the room. A good joke loosens something. Importantly, a good joke reminds you that private agonies are also common and therefore survivable. A good joke is not a cure. You are just free for a moment from the demand to be healed.

Because most people are under the mistaken impression that comedy is the “low” form and tragedy is the high, they think “more human” comedy is “elevated” comedy. You don’t even need to be an Aristotelian to know this is wrongheaded. Judge this artistic strategy by its desiccated, unappetising fruits. *cough* Nanette *cough*

Comedians and their audiences are not patients to be nursed, or even friends with whom to commiserate. We’re all simply funny little mortals.

Bro used a photo of Hannah Gadsby before she was 100kg?? 😭

Great piece. Definitely a worthwhile reminder for humour writers.