The Wilde Child Grows Up

An essay on Oscar Wilde for his 171st birthday

I’m indebted to Oscar Wilde. So are you. Even if you’ve never seen one of his hilarious plays, read one of his exquisite short stories, his singular novel The Picture of Dorian Gray, or his sharply sculpted critical essays, you’ve felt his influence. Wilde is partly responsible for a modern assumption so ingrained we scarcely notice it: style matters and a life can be justified, if not redeemed, by beauty.

He popularised the pursuit of aesthetic experiences, enjoining us to attend seriously to matters of style over matters of substance. “It is only shallow people who do not judge by appearances,” he quipped, scandalising Victorian moralists who believed art must be edifying and useful. Wilde’s heresy was to insist that appearances aren’t merely decorative but constitute life’s meaning.

One might glance at our culture and assume beauty and style have already been given their due. We live, after all, in a world of surfaces. Scrolling through Instagram, we encounter perfectly framed selfies, latte art, and homes curated like museum vitrines. A cynic might say we live in Wilde’s promised aesthetic republic, and that its reign is vacuous.

But the glamour of Aestheticism outshines the glossiness of the algorithm. The former recognises beauty as a cultivated relation to the world while the latter reduces it to a consumable. Wilde’s worldview, far from being mere indulgence, was a philosophy of form that sought to elevate life itself into an art.

The philosophy of Aestheticism—“art for art’s sake”—emerged in the 19th century as a revolt against the idea that art’s value lay in its utility. Figures like Walter Pater and John Ruskin (in his more lyrical moods) helped shape the doctrine, while Joris-Karl Huysmans in France furnished its decadent extremes.

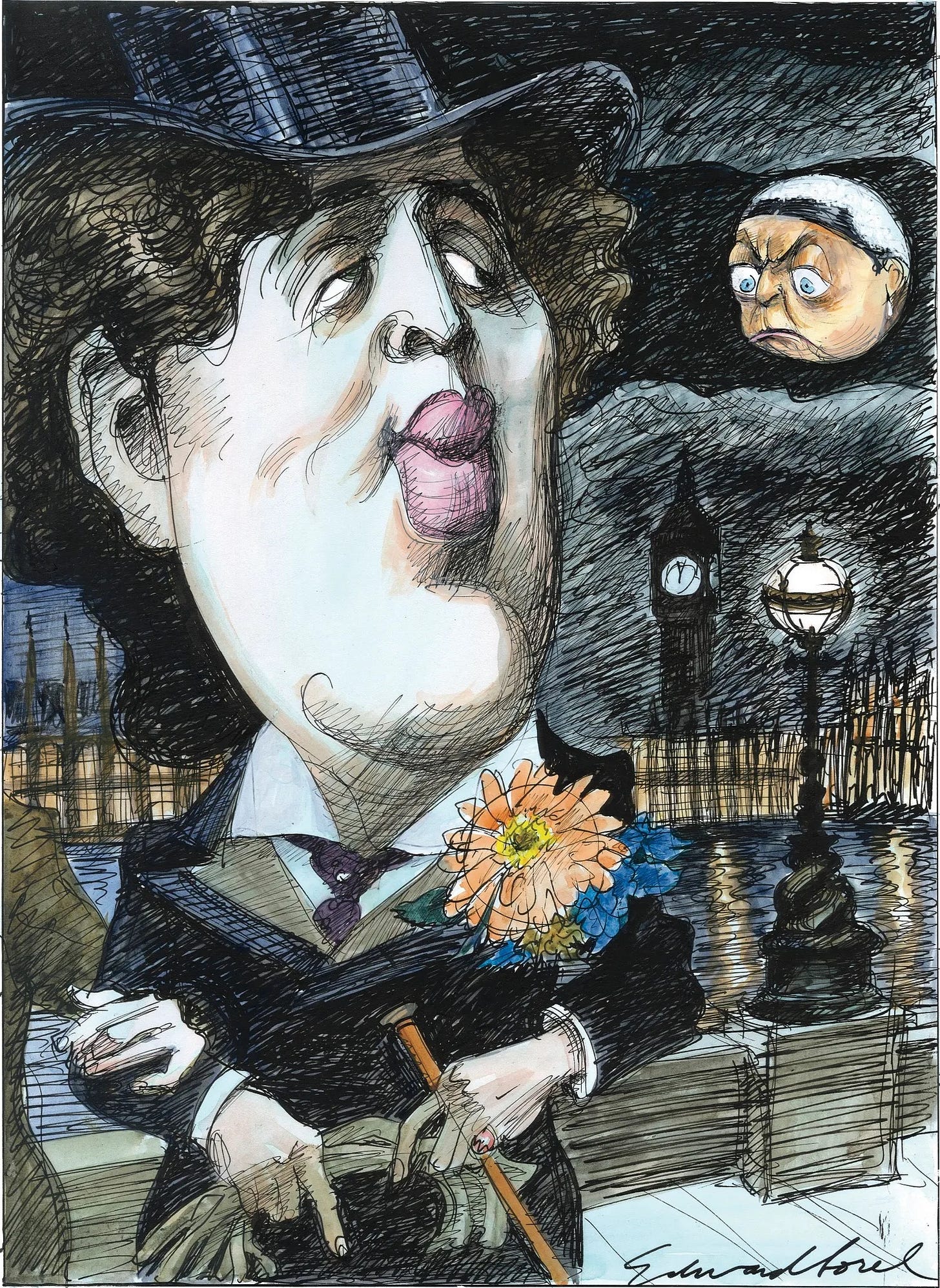

Wilde synthesised this with his Oxford education in the Classics and the sensibility of the French Symbolists. Out of this, he crafted a uniquely English dandyism: wit in the salon, lilies in the buttonhole, long hair, silk cravats, and so on. He also wielded paradox as a weapon against dreadfully solemn intellectuals and society types in fin de siècle London.

To its detractors then and now, Aestheticism is an empty creed, luxuriating in lilac-scented idleness, a philosophy of cushions and champagne flutes. But to jettison substance in favour of form, to insist the how of a thing outweighs the what, is itself a substantive position. Wilde’s aphorism that “all art is quite useless” is a declaration of autonomy. Beauty needs no alibi, nor do its appreciators.

The aesthetes argued that moral instruction and political messaging burdened art. They proposed instead that the experience of beauty (whether in a painting’s composition, a line of verse, or the perfect cut of a suit) was a good in itself. Dandyism, in this sense, was not just fashion but a form of disciplined attention that insisted even the self might be composed as a work of art.

Despite Wilde’s claim that art is “neither moral nor immoral,” his Aestheticism is, I have come to believe, profoundly ethical. When I was in my twenties, I was drawn to Wilde because I mistook his stance for a flight from morality. Morality is never of the young but always for the young, imposed by elders as a system of prohibitions. It often appears as a hostile force, an attempt to legislate the terms of one’s becoming.

Wilde’s epigrams and paradoxes, his glittering refusals to be pinned down, felt like an escape hatch. His most famous device, paradox, suffuses everything he wrote. Paradox is a way of holding opposites in tension, of destabilising solemn truths. “The pure and simple truth,” he observed, “is rarely pure and never simple.” When I was younger, I used to hang this quote above my writing desk.

Wilde openly states there’s a deeper honesty in our masks and affectations. The masks we wear reveal more about our souls than the authentic self, which is just another mask, according to this view.

The notion that surfaces can possess an ethical weight runs counter to our current obsession with authenticity. We are exhorted to be “real,” to bare our souls online, to declutter our homes and psyches until only some essence remains. But Wilde teaches the opposite. In deliberate self-fashioning, we find freedom.

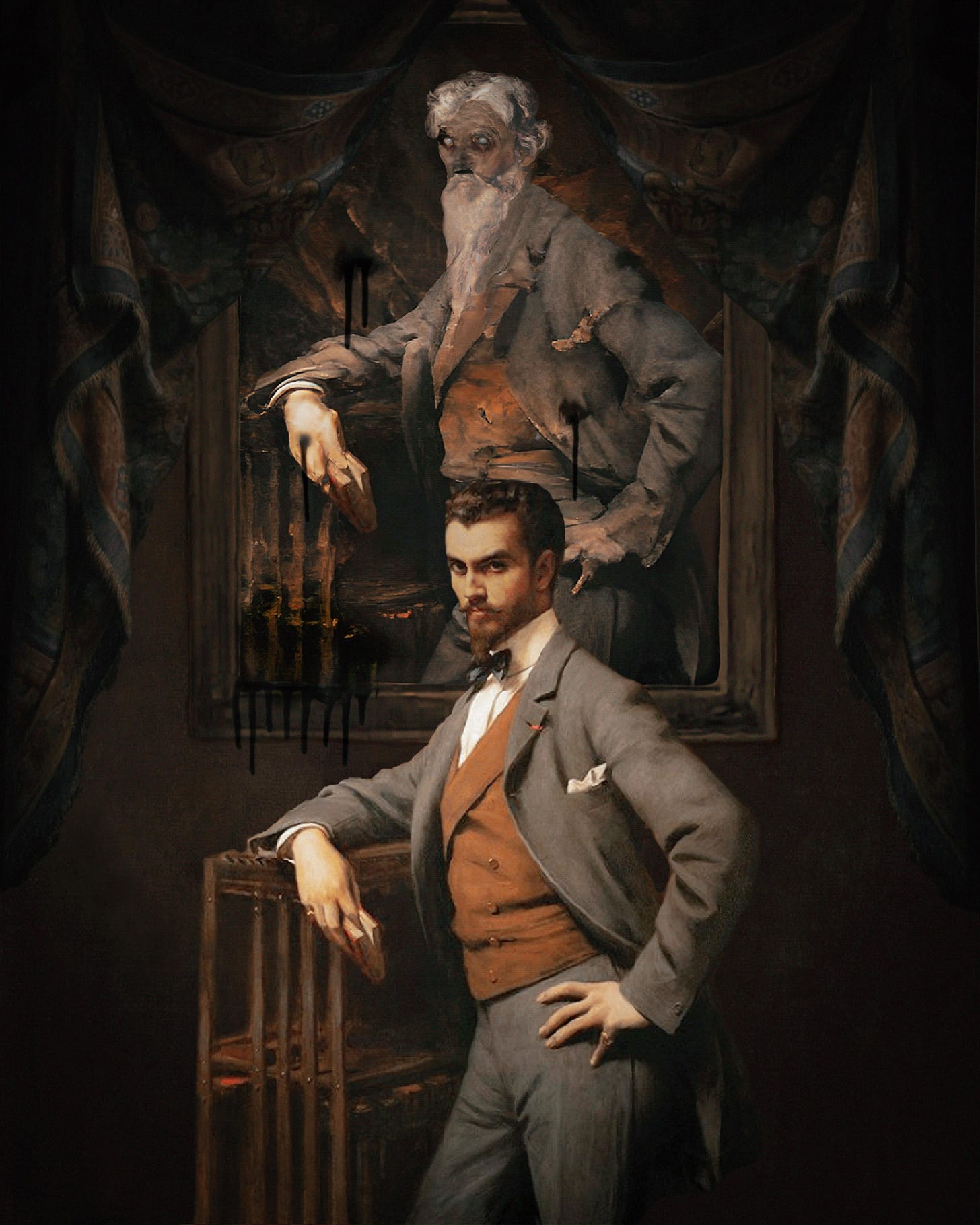

But unbridled freedom doesn’t necessarily lead to the good life. Wilde’s most famous character, Dorian Gray, is a beautiful young man who becomes recruited to the aesthete’s world. Charmed by the Aesthetic philosophy, he decides to pursue nothing but sensation, pleasure, the finer things in life. The lifestyle corrupts him, ultimately turning him into a murderer. Through it all, he remains physically beautiful while his portrait in the attic rots and decays.

Wilde’s novel is often interpreted as a cautionary tale against Aestheticism itself. But it’s also an extended study of the hypocrisies of unlimited freedom. You cannot escape the moral weight of your choices, no matter how hard you justify them through your ideology. Beauty will not save you. And in any case, Dorian is not actually pursuing beautiful things. Beauty is the post-hoc justification for every selfish act he commits. The horror of the novel comes from the perversion of beauty via a kind of Satanic libertinism.

There is a tendency with discussions about The Picture of Dorian Gray to view it as a reaction to Victorian moralism. This tendency is helped along by the foreword, not present in the first edition, but added later by Wilde as a way to justify the book’s contents.

There is no such thing as a moral or an immoral book. Books are well written, or badly written. That is all - Foreword of The Picture of Dorian Gray, Oscar Wilde

Wilde wasn’t trying to scandalise Victorian England by celebrating Dorian’s immoral actions. He was showing how even reacting to your epoch’s moral panics makes you a slave to them. Even having to say “art for art’s sake” cedes ground to the moralists. Moralism is frustrating, especially for artists who want to push boundaries. An endless hedonic abyss is worse than frustrating, it is often the end of your artistic career and sometimes the end of your life. But these aren’t your only choices.

Aestheticism offers the thrill of turning away from moralism, of choosing beauty as one’s banner rather than being conscripted into someone else’s idea of virtue. Wilde was the great herald of this impulse, but he didn’t accept it uncritically. Dorian Gray is enough proof of that. Even so, Wilde was committed to many elements of Aestheticism until his downfall. After his trial and imprisonment, he was never the same. Broken and humiliated, he died relatively penniless in Paris in 1900. He was only 46. Had he lived longer, he likely would have disavowed Aestheticism entirely. Because once you get to middle age, you realise the spiritual poverty of a lot of your previous aesthetic commitments.

One contemporary of Wilde’s, who lived until the 1960s, was W. Somerset Maugham. I have been reading a lot of him lately and I keep comparing the two. Maugham has a maturity and lucidity that I feel would be simpatico with Wilde had he survived into his 50s and 60s.

Maugham understood what Wilde perhaps couldn’t afford to openly admit: “art for art’s sake” is itself a mask. Wilde wore it defiantly while Maugham learned to look through it. Maugham began his career in the theatre, and like Wilde, was one of the few modern playwrights to have several of his works showing at the same time. But it was in his novels that Maugham did his best work. His fiction is suffused with a mature, clear-eyed recognition that artifice, while powerful, cannot shield us from the ordinary dramas of human need.

This insight is most mercilessly deployed in Cakes and Ale, his sharpest satire of literary and artistic posturing. The narrator, William Ashenden, has a monologue in the middle of the book about the aesthete, and you can’t help feeling Maugham’s exasperation after a long life dealing with these kinds of people. “Beauty is a blind alley. It is a mountain peak which once reached leads nowhere,” says Maugham via Ashenden. “Beauty is that which satisfies the aesthetic instinct. But who wants to be satisfied? It is only to the dullard that enough is as good as a feast. Let us face it: beauty is a bit of a bore.”

Cakes and Ale takes the criticism even further, suggesting that art for art’s sake is not some evacuation of morality or politics, but that it serves just another, darker utility. The novel revolves around the death of the eminent writer Edward Driffield, whose reputation is being meticulously stage-managed by Alroy Kear, a preening, self-important literary operator who wraps himself in the language of taste and refinement. Kear is writing a literary biography on Driffield, a writer that Ashenden knew in his youth. Kear sidles into the narrator’s life, arranges a series of meetings before he finally asks Ashenden for his thoughts on the famous writer. The narrator gives a warts and all account of Driffield’s life, particularly his liaisons with a lower class lass, who happens to be the loveliest person in the entire story. Kear, however, is confronted by these “unsavoury” details and chooses to omit them from his book. It is clear he decides to do this for his own reputation as much as Driffield’s.

He claims to be safeguarding Driffield’s dignity, but in reality he’s building a shrine to himself. His brand of Aestheticism is less about beauty than about control, sanitising the past, and airbrushing complexity. He wants to construct something appealing but ultimately incomplete. The book may be well-written but it will be timid in its observations.

Maugham skewers him without raising his voice. There’s no melodrama, just the steady, pitiless gaze of someone who has spent a lifetime watching how people behave when they put on the aesthete’s mask. Kear is Wilde’s dandy grown into something smaller and meaner: an aesthete whose ideals are merely manoeuvres. The language of beauty has become a tool for clout-chasing.

This is why Maugham feels like Wilde aged into precision. To embrace Wilde is to learn the art of making the mask. To read Maugham is to recognise when the mask has become too comfortable.

Aestheticism, in other words, is an adolescent fixation and Maugham offers its adult reckoning. But this isn’t a repudiation, it feels more like maturation. Wilde gives us the courage to invent ourselves while Maugham gives us the clarity to look at what we’ve invented. Maugham is unflinching and lucid in his observation of human nature. He doesn’t let high-minded ideas of “art for art’s sake” get in the way of what needs to be said.

I often wonder what Wilde’s career would have looked like had he lived longer. What would he have made of the twentieth century? It is one of the great literary “what ifs?” But I do know that he would have left behind Aestheticism and its militant “art worship.” I get the sense he would have made a Maughamian turn, using his powers of wit and phrasing to observe people as they are, not as players in a masque. He was already on the way there.

In one of his final pieces of writing, De Profundis, Wilde has a section where he comes to see the limitations of worshipping art at the expense of the forces that exist out in the world. Ordinary people are worthy of appreciation, and uncritical bureaucrats are worthy of your disdain, he says. Art for art’s sake can distract you from these more everyday sites of inspiration. I read this section and like to imagine Wilde surviving, writing more, and making a clear-eyed turn towards the world instead of escaping into art:

Charming people, such as fishermen, shepherds, ploughboys, peasants and the like, know nothing about art, and are the very salt of the earth. He is the Philistine who upholds and aids the heavy, cumbrous, blind, mechanical forces of society, and who does not recognise dynamic force when he meets it either in a man or a movement.

Very cool article. I understand Maugham's exasperation with the dandies, but I feel he didn't consider an option beyond Wilde's death or Huysmans' flip to the cross. Instead, create a flow that allows time outside the world of the Aesthete, then, as we say, "renew sinning with refreshed vigor"

Looks like I need to read some Maugham...