FICTION: "Derivé"

An extract from my satirical "throuple" novel, Magic Number

Gentle sunlight greeted him as he left the house for a morning drift.

A drift is not a walk. Walking is utilitarian and mechanistic. Instead of setting a destination, Ravi liked to let the world take him where it would. ‘Like flotsam on the sea,’ he explained to Gus once, who replied, ‘what the fuck is flotsam?’

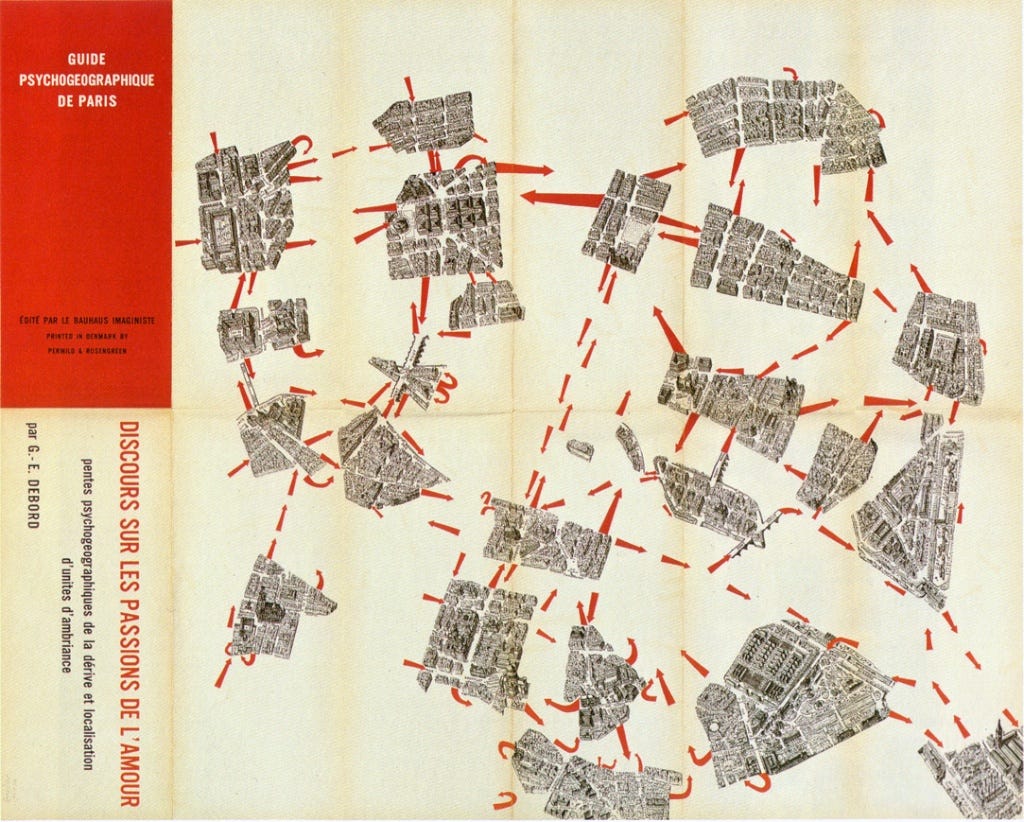

Ravi pinched the idea from Debord—drift, or derivé, if you want to use the fancy French term (and he did, mostly at parties, always at seminars), was his intellectual justification for wandering. You let go of your everyday patterns of travel, your usual ways of navigating space. This is best suited to cities, where there are multiple ways to get somewhere. A creative response to the urban environment, you wander without purpose, but also let yourself be shaped by the wandering. One day you head north on one street, and the next you decide to take a southerly direction, or you turn off that street onto a laneway the day after.

It certainly kept his walks fresh, and helped unlock things in his mind. It was his meditation. Regular meditation was out of the question—he had been too traumatised from his mother’s attempts to make him do it. He had given up trying to interpret her batty logic, but you don’t even need common sense to realize a ten-year-old is incapable of practicing Vipassana.

‘You were conceived in the ashram, you should be better at this,’ he remembered her saying after he’d started crying.

Drift took him south into Brunswick. Lost in thoughts about the book and his future, he almost ran into a man on a fixie. Later, he passed a portion of nonnas or yiayias—he found it hard to tell the difference between Greeks and Italians, especially when they are tiny old women. Gus often made fun of him for this: ‘we all look alike to you, huh?’ Some nonnas or yiayias hosed leaves from their concrete driveways, other nonnas or yiayias picked at lemons and olives. Everyday life was not an astute writer, seemingly unaware of such ethnic cliches.

It was easier to drift here than in Kew. There was more order and staleness in the upper-middle class streets he grew up in. But north of the Yarra, the mélange of cultures and the clash of architectural styles—ornate nineteenth century shop fronts opposite gaudy wog mansions, 90s townhouses, and the sleek demenses of gentrifiers that looked like they should be galleries of modern art—were a constant delight.

Drifting is better suited to spaces not places. There is a difference. A space is a pre-condition for place, but they are not the same thing. Space is physical, place is meaningful. It’s the psychological and emotional content we give to our environments. It becomes hard to be subject to streets and paths you know so well. To drift is to fill your movement with meaning, to change your surroundings from a space (blank, foreign, potential) into a place (arresting, evocative).

Before Brunswick became a place to himself and other new Australians, it was a significant place for the Woi wurrung people. For thousands of years, sacred rites, business, and gatherings were all performed here, mostly around the still-picturesque Merri Creek. Then colonial roads connected villages and villages joined into townships, coalesced into the city. And through it all, more names and more meanings into the accretion that is place.

He was drawn down to Sydney Road, its ambient din penetrating the music blaring through his headphones. His pace slowed as he went past the sari shop and he drank in the ambrosial scent of sandalwood. In rare melancholic moods, he would stop and peruse the colourful fabrics and how they draped elegantly over the mannequins, imagine the faces of relatives he would never know, and which of these styles they preferred. But he didn’t do that today. Instead, he kept heading south.

Soon after he crossed to the other side of the road, he felt a tap on his shoulder. Kit was clopping behind him on chunky-heeled boots, holding a linen tote bursting with books.

‘On your way to work?’ he asked.

‘Sort of. Didn’t want to go into campus today, felt like working in the cafe. How have you been? Haven’t seen you since…’

‘Your birthday party,’ he said.

‘Oh God, we got loose, didn’t we? Has it really been that long? I’ve just been occupied with work. And by work, I don’t mean research, I mean endless admin. The life of the contemporary academic, huh?’

‘Looking forward to having all that admin one day.’

‘Well, speaking of which…’ She inched closer, took him to one side of the footpath and hunched over in that conspiratorial way whenever she had some juicy tea to spill.

‘There’s going to be a new job coming up. You should apply. I’ll be on the selection panel. Of course, I can’t really say I’d favour you over anyone else, but…I’d favour you over anyone else,’ she smirked.

‘That sounds great. Know anything else about the position?’

‘Come have a coffee with me. I’ll tell you all about it.’

They walked down to a cafe a few streets away from Sydney Road, sat down and ordered. Ravi got a flat white and Kit ordered a cappuccino and a pastry. The position was a fixed term contract for two years, but was full time, so had all the benefits of a proper academic position. She said that it would most likely be upgraded to a full time position when the two years were up.

‘These don’t come along so often now. But I think you’re in with a shot,’ she said, winking at him.

‘I’ve applied for so many jobs and never get them. Even the ones that line up perfectly with my expertise, can’t even get interviews.’

Kit sipped sheepishly from her cappuccino, silky foam forming a tiny beak at the top of her lip. ‘Yeah, it’s tough at the moment. Especially with these bloody Tories pulling funding from the system all the time. This one’s a bit more open though. I think you’ll ace it, if you know what I mean. Oh, I shouldn’t be saying that.’

‘I hope so,’ he said. ‘When is it being advertised?’

‘Soon. I’ll send you a link when we upload the job posting. Anyway, how are you doing?’

‘Just plugging along with the book.’

‘How are the boys?’

Whenever they met up now, it was a matter of minutes before Kit brought up his love life. Prior to adding a third, she took no interest in his relationship. ‘They’re great.’

‘I just don’t know how you manage it.’

‘Manage what?’

‘Oh, writing a book, teaching, marking student papers, and having two boyfriends. I’m flat out without a relationship. They tend to slow me down. Wouldn’t have the career I have now if I had a husband as well,’ she cackled.

‘There are advantages, I guess.’

‘Like?’

‘Well, you know, Gus has always kept me grounded. He isn’t as educated, so if I can’t explain a concept to him, I feel like I haven’t grasped it very well. Also, he does all the housework. Which is a relief. I can spend a lot of my time focused when I work from home, not get distracted by laundry or dirty dishes. And Dylan? Well, he stimulates me—no, not just in that way, get your mind out of the gutter—it’s his way of looking at things. Guess that’s why he’s such a creative photographer. He’s helped me brainstorm a ton of ideas. It’s been great having him around lately.’

She scoffed at him. ‘Are they you boyfriends or your secretaries?’

‘You brought it up,’ Ravi said, crossing his arms.

‘It’s an unusual set up, you got, that’s all. I’ve known a few people who’ve had polyamorous relationships. They’re…difficult.’

‘Most relationships are difficult,’ he said, a bit too defensively.

‘Oh, no doubt,’ Kit replied. ‘Doesn’t it get…knotty with three people?’

‘Knotty?’

A coquettish smile over her coffee cup. ‘I didn’t want to say difficult again. First thing I found in the mental thesaurus.’

‘Sometimes there are arguments over what to have for dinner. Or which bar to go to.’

‘It’s all bliss then?’

‘Well, of course not. There’s the thing with Gus, which we’ve talked about. I’ve adapted to it, it doesn’t bother me as much as it used to. He needs time, that’s all. I don’t want to force the issue.’

‘Weren’t you worried about introducing a third person into all this drama?’

‘If anything, Dylan is the more dramatic one. Anyway, Gus’ drama is more muted. He’s most of the way there. His mum—her knowing—is the last hurdle.’

There was something to the way she was looking at him. Not disapproval, but something like it. Not pity, but something like it. She had this look when they talked about Gus before. It was subtle. Fleeting, microscopic twitches of judginess specific to women of her age and class. She’d never vocalize any doubts, of course. It wasn’t just the typical Anglo-Australian reticence to avoid conflict, it was also because she was a lecturer in an Arts faculty. And to openly question ‘unconventional’ modes of life was a cardinal sin. He would never call her out on it, especially now she had the power to get him a full-time job. Like most academics she was outwardly and sincerely socially progressive, but subconsciously probably didn’t approve of the way Gus was handling his life, of the way Ravi was putting up with it, of the way they stirred in the complicating factor of Dylan.

With a bleeping email notification, her phone materialized in her hand and she expertly replied one handed while she took another sip of coffee. Ravi lifted himself out of the chair and said, ‘I’ll leave you to it then, good to see you.’

‘You too. Oh also…when you apply, make sure you mention you’ve got a book contract,’ she said, before another volley of clicking sounds from her phone.

‘Oh, I’m planning on sending it off to press soon,’ Ravi lied. He was nowhere near finished, but if he gave the selection panel the impression that he would have a book out soon, that could make him competitive. If there is one thing you really need to be in academia, it’s competitive.

‘Excellent. I can’t wait to have you on full-time. Oops, I did not say that.’

He smiled at her. ‘I better go and finish this book then.’

Ravi didn’t drift back home, carried through the streets like flotsam. He marched, brisk and with purpose.