Celluloid Catechism

What We Can Learn from the "TradCath" Origins of the Production Code

In the early 20th century, before Hollywood became Hollywood, America was already hooked on the movies. By the 1910s, there were more than ten thousand nickelodeons and storefront theatres flickering across the United States. These weren’t the grand “picture palaces” of the Roaring Twenties: many were dingy back rooms, barely converted from retail. But they were cheap, accessible, and open all hours. That made them dangerous.

To whom? Reformers, mostly. Even before film had a name for itself, it had censors. And while the Catholic Church would later make Hollywood kneel with the Production Code, the first wave of moral panic came not from Rome, but from the Progressives.

Film, in the Progressive view, was a new kind of vice; akin to the saloon, the brothel, the burlesque hall. Worse, it was popular. It reached children, immigrants, the poor, the unsupervised. To the reforming classes, it was a vector for corruption, just as dangerous as bad milk or tenement air.

The early 1900s saw various attempts to institute state-based censorship boards drawn from the community or self-regulating industry bodies. Few of them got very far because there were constant challenges, mostly from Progressive groups, or else from religious (predominantly Protestant) authorities. Many of these boards checked all motion pictures before they were permitted to be legally screened.

From the Progressive viewpoint, such pre-censorship was entirely justified because it measured a film’s content against any ill social effects it might have on the community. To such arbiters of public morality, the regulation and censorship of movies were continuous with the broader project of government regulation of education, child labour, sanitation, and food safety. Censorship would protect the public’s moral fiber in the same way food and drink legislation protected against disease and addiction.

The effect of such state and municipal boards was that much of the cheeky, risqué sensibility present in very early silent films disappeared, but producers still managed to sneak in some sin to pass the censors.

But after the Supreme Court of the United States ruled in 1915 that the constitutional right of free speech did not apply to the medium of motion pictures, full-scale censorship became inevitable.

The President of the Motion Picture Producers and Distributors of America (MPPDA), Will Hays, had taken office in 1922 and was often required to persuade the various boards not to censor particular films. As someone who argued against censorship, it is ironic that Hays’ name is often attached to the Production Code.

The MPPDA wanted to avoid a situation where a patchwork of censorship boards ruled things appropriate or inappropriate for exhibition because such a situation would be bad for business. One film banned in one municipality might be available in others, which would result in an unpredictable flow of ticket sales. Because Hollywood borrowed heavily to finance its productions, any disruptions to ticket sales would be catastrophic.

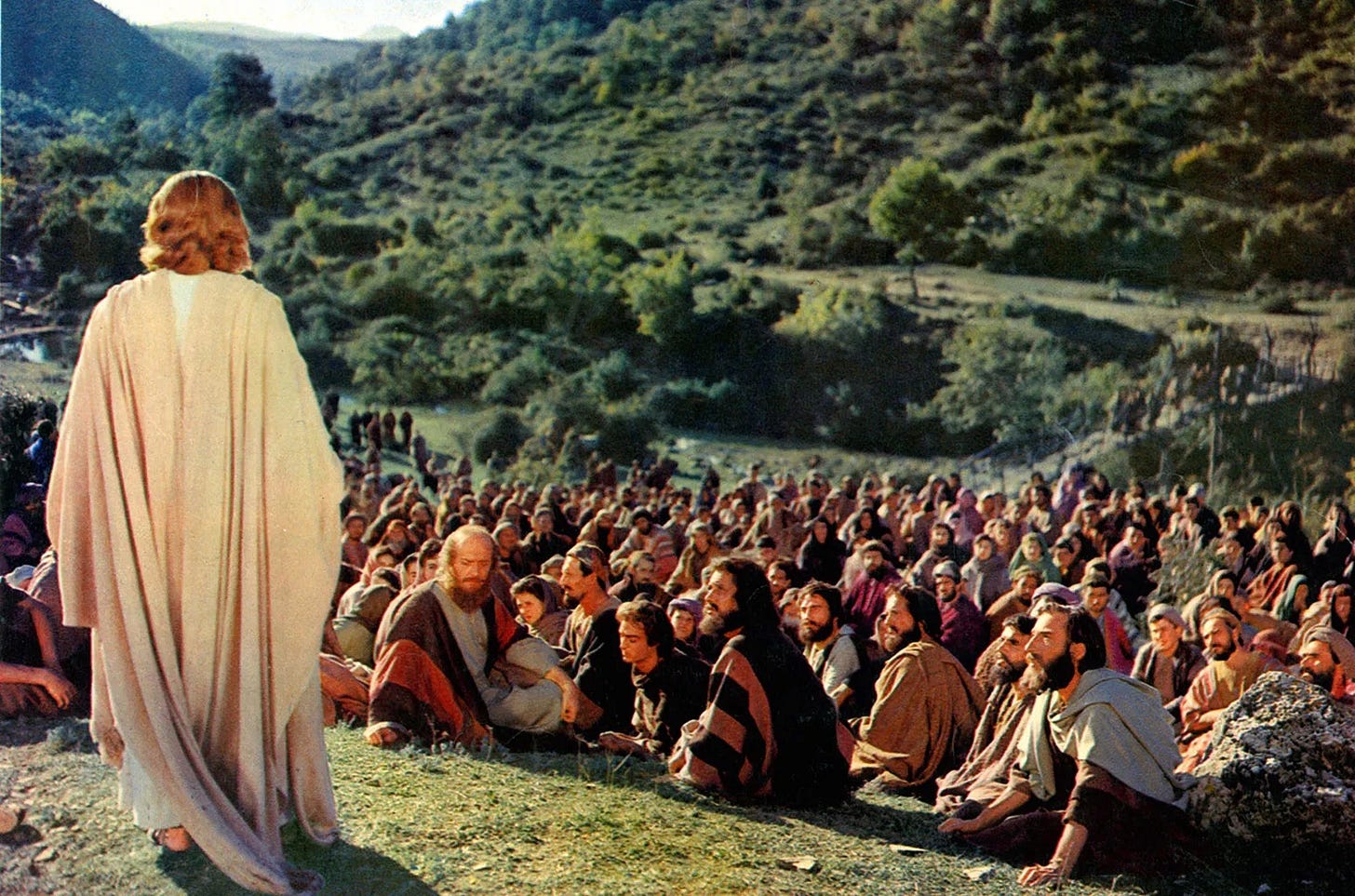

The United States was (and is) a predominantly Protestant nation. So it is a strange quirk of history that Catholicism had so much to do with the development of the Code. Enter Martin Quigley and Father Daniel Lord. Quigley was a film trade publisher. Lord was a moralist with a flair for drama (and incidentally, an adviser on Cecil B. DeMille’s The King of Kings). Together, they drafted what would become the Motion Picture Production Code. And with it, they smuggled Catholic moral theology into America’s most secular artform.

The Code made much of the fact that movies were not, like opera or poetry, for the cultivated elite. Cinema appealed to a more democratic audience. It was “for the cultivated and the rude, the mature and the immature, the self-respecting and the criminal.” This accessibility was precisely what made film so suspect.

The Code’s ethos mirrored that of the Church’s Index Librorum Prohibitorum, the list of banned books. But it went further. Unlike the Index, which judged a work after publication, the Code operated preemptively, policing scripts before a single scene was shot. It was moral surveillance in the planning stage.

Studios grudgingly agreed to the Production Code, though they didn’t take it as gospel. Lord and Quigley were under the impression that the Code would be rigidly enforced, while producers saw it merely as a loose guideline. The studios pushed for a concession of which Lord and Quigley seemed unaware; that a panel of producers could overturn any censorship or cuts that the MPPDA recommended. In practice, this gave the studios significant leeway, much more leeway than Lord and Quigley were willing to give when they wrote the Code.

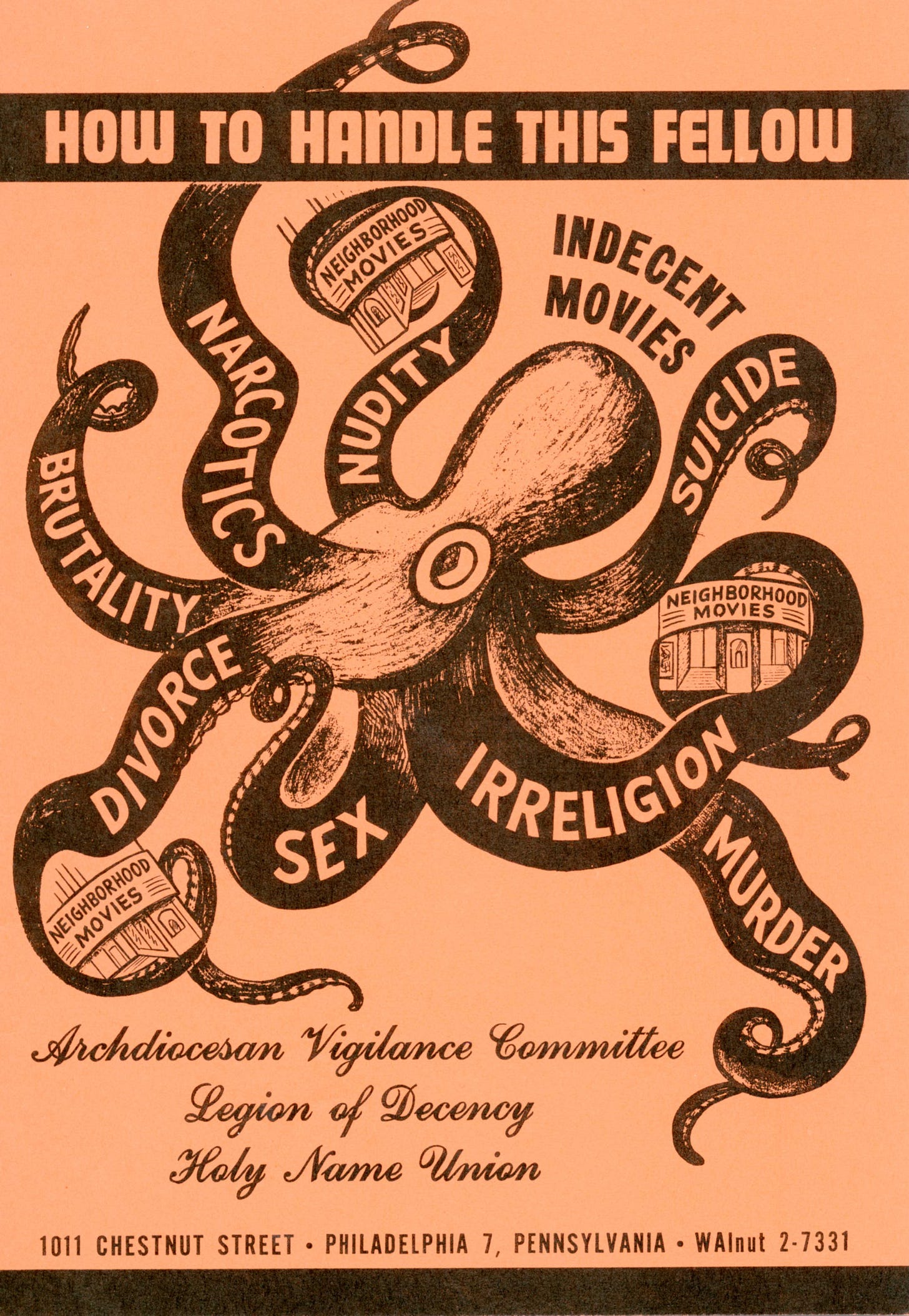

The effects of the Depression in the early 30s meant that studios could not risk ticket sales by constraining themselves to the extent the Catholic crusaders wanted. Plenty of sexual and moral contraventions of the Production Code got through. Lord, Quigley, and a whole host of other Catholics were furious. By 1934, the Catholic hierarchy had formed the Legion of Decency. Having played a crucial role in this, Lord and Quigley made good on the threat of Catholic backlash that Hays and others in Hollywood had worried about. The national organisation of bishops boycotted films directly from their pulpits, and the Catholic media followed suit.

Hays pushed for detente by creating the Production Code Administration (PCA) and appointing Joe Breen (a devout Catholic) as its director. The PCA’s powers eliminated the panel of appeal and all scripts had to be submitted to Breen before production, then the final film product needed to be seen by him before he would grant the film a PCA seal for distribution.

The Legion continued to publish lists of prohibited films and some bishops made their congregations pledge not to see immoral movies, claiming that to do so was a mortal sin. The Production Code would remain in effect for over thirty years, with Breen overseeing it for much of that time.

The constraints of the code weren’t all bad. They were at least partially responsible for cinema’s development into a sophisticated, serious art form. Not being able to blatantly show sex, certain types of criminality, or questionable morality forced filmmakers to approach these topics in a circuitous, nuanced way. Subtext became acutely honed in this period, as did a certain richness in acting and cinematographic styles. Simple moral tales allowed for innovation in other areas.

Once the code ended 1968, there was an explosion of sex and swearing and violence with the New Hollywood filmmakers. This returned the movies to the sort of carnivalesque vibe they had in their infancy, but to a maximal degree. Such aesthetic explosions are always refreshing and exciting. None of this is to say that the Code was a necessary evil, but its legacy is more mixed than people tend to appreciate.

While I am no way sympathetic to censorship of any kind, there is a strange lesson to take away from the decades-long Catholic meddling in cinema. Quigley and Lord didn't just complain about cultural decay. They acted. They imposed a vision (however flawed) on an entire industry.

In our age of aesthetic enshittification, we might consider this: it doesn’t take a majority to set a standard. In fact, there is an argument to be made that the majority shouldn’t have any say in setting the standard. Attention seems to rule aesthetics at the moment. And attention is democratic. And what gets attention right now is either artistically moribund or spiritually repulsive or both. In short: slop. The people need to be guided away from slop.

We can do more than simply “notice” that culture is degenerating. We can do something about it. Of course, I don’t mean fashioning censorship regimes. I mean that you only need a few diligent, determined people on the same page to influence an industry, an artform, the culture at large.

And this is a weirdly inspiring element behind the Hays Code era.